TL;DR Summary:

America’s first rehabilitation center, known as the New York State Inebriate Asylum, opened in 1864. It offered a radical alternative to the punitive approach toward inebriacy. Spearheaded by Dr. Joseph Edward Turner, the facility aimed to treat alcoholism as a medical condition. The center emphasized not only labor and good morals, however, but also the spiritual enlightenment of the patient. Yet the Inebriate Asylum, with its Gothic architecture, symbolizing hope and redemption, only made it 22 years. It treated inpatients for the space of a decade (1864-1874). Still, the Inebriate Asylum laid the foundational stones for modern addiction recovery methods.

The story of America’s first rehab center, the New York State Inebriate Asylum, is a dark and illuminating tale of human frailty and societal progress. It is a story born of desperation and hope, of human suffering distilled into a clear purpose, and of a grand experiment that dared to challenge the popular ethos of condemnation and to offer the promise of redemption instead.

The Era of Moral Certainties

At the edge of modernity in the mid-19th century, America, swollen with ambition, seemed to be making unprecedented strides in industrialization. Yet somewhere in this shiny, gilt modernity, a quieter and more insidious crisis was unfolding: alcohol was ravaging families and communities.

The mid-19th century was intoxicated by the promise of progress but underneath this veneer of growth, a national crisis was emerging. “In the half century between 1820 and 1870,” writes historian David Gutzke, “the nation’s consumption of absolute alcohol increased from approximately 4.7 gallons per capita to about 8.2 gallons.”

The Visionary Catalyst

This landscape of despair was entered by Dr. Joseph Edward Turner, a physician whose vision was as radical as it was compassionate. Turner, informed by a blossoming movement in Europe to treat alcoholism as a medical condition and not a moral failing, had a revolutionary proposal: an asylum dedicated solely to the care and cure of inebriates.

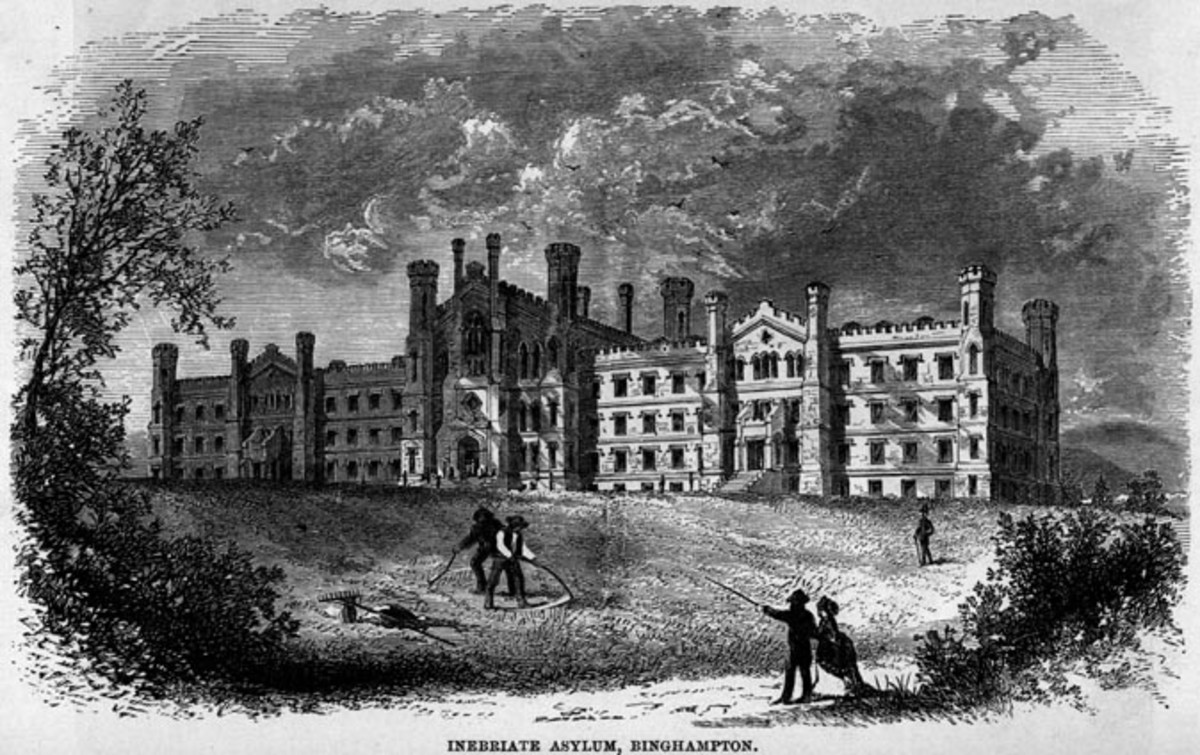

In 1864, the doors of the New York State Inebriate Asylum opened in Binghamton, New York. To even create such an institution, then, was a splendid act of defiance. It was a declaration, implicit but clear, that the addicted were not an irredeemable class but human beings deserving of dignity and care and far better treatment than what the typical asylums off to (and, in fact, much better than what so many addicted people now receive).

An Architectural Metaphor for Redemption

The mission of the asylum was as ambitious as its physical design. Isaac G. Perry created it in the Gothic Revival style though it was more than a mere structure. The asylum was a potent emblem. Its towering spires, intricate stonework, and sprawling, landscaped grounds embodied the era’s optimism a conviction in the power of the environment to elevate mankind.

The cathedral-like asylum was intended as much for the spirit as for the body. Its architects and patrons understood that recovery required more than medical care; it required a kind of spiritual revival. The building was meant to be itself a kind of medicine a grand, beautiful antidote to despair.

The Treatment Philosophy: Labor, Morality, and Purpose

The belief in the remarkable, even miraculous, power of labor to redeem was close to sacred in the asylum. Patients worked; they were not like the poor, relying on the dole. Somewhere between the work of the lay brothers of the Trappist monasteries and the efforts of the Shakers, the almost meditative work of the inmates was intended to keep them from dwelling on their sorrows and in their old ways. It was not busywork. Work was supposed to be good for the soul. Fasten A to B, then B to C, and so on. Keep the body moving, and keep the mind occupied.

At the heart of the institution’s philosophy was moral therapy, which attempted to reawaken a sense of responsibility and ethical alignment within the patients. The asylum’s leadership believed that addiction was as much a spiritual crisis as it was a physical ailment. They encouraged patients to confront their failures and to imagine a better self, as a means of attempting to rekindle human potential.

A Dark Glamour

Nonetheless, the New York State Inebriate Asylum has a story that carries more than its share of shadows. Some who should have understood better criticized the asylum. They called it an excuse for prohibition, an institution that indulged the inebriate and one that misguidedly mirrored prisons, hard labor, and the kind of punitive justice that civilized societies should have forsaken. Moreover, despite lip service to the idea that alcohol was a disease, the asylum’s medical staff often behaved more like prison guards than healers. Indeed, the autocratic way that the asylum’s superintendent ran his institution seems to have served whiskey more than the patient.

The Legacy: A Seed for Modern Redemption

The asylum finally shut down in 1879, its big dream dimmed by money problems and changing social priorities. But its lasting influence is undeniable.

It set the stage for future ways of dealing with addiction, its principles living on in institutions like Alcoholics Anonymous, which surfaced in the 20th century with an almost exact replica of the asylum’s setup: a group of men (with a few women) who had gone to hell and back when it came to alcohol, meeting regularly to share their unsanitized life stories in the service of reconstituting and strengthening their individual and collective moral character.

More from Fun

You Won’t Believe What People Are Googling: Auto-Suggest Nightmares

Without a doubt, Google autocomplete is one of the most illuminating windows into the human psyche. It’s not some cold, …

Seeing Faces in Everyday Objects? Here’s What’s Really Happening

Human cognition is both a marvel and a mystery. It is a tool forged in the fires of evolution, honed …

Can You Tell If This Art Is Human or AI? Most People Can’t!

Once upon a time, art was the way humans flexed, a way to show off our emotions, imagination, and skill. …