Pinocchio’s Deceptively Simple Myth

One might first regard the tale of Pinocchio as a quaint children’s story, a simple parable about a wooden puppet’s transformation into a “real boy.” However, if we examine it closely and truly grapple with its mythic structure and symbolic narrative, we find that Pinocchio is saturated with the archetypal motifs and moral lessons that have, throughout centuries, served as the foundation for human character formation. It is not merely a charming fantasy; it is a deep, symbolically-layered account of the individual’s psychological struggle against chaos and deception, guiding us toward truth, responsibility, and proper moral orientation in the world.

The Wooden Origins: Tradition and the Individual

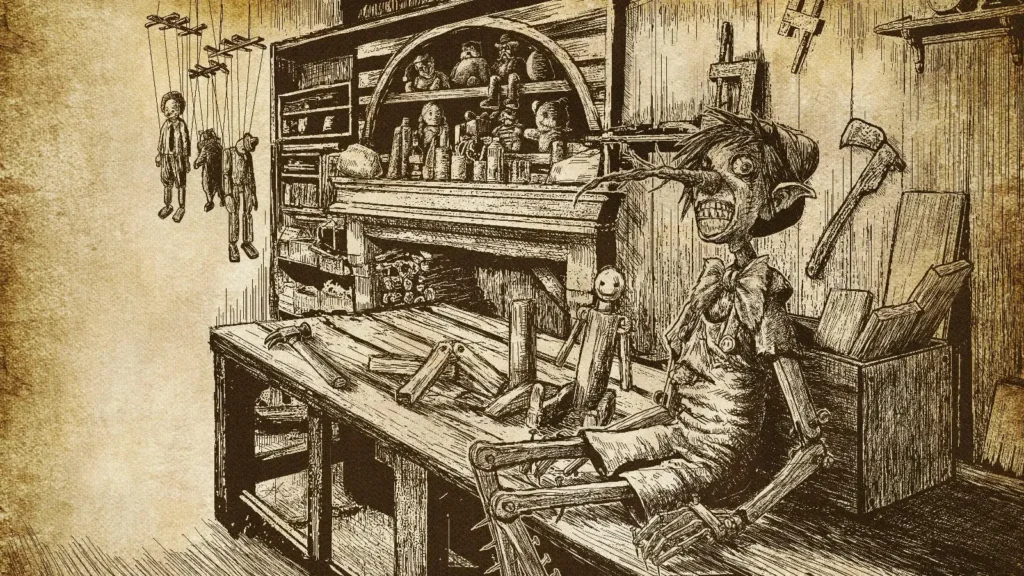

To begin, consider Pinocchio’s origins. He is carved from wood by Geppetto, a humble craftsman. The wooden boy, artificially constructed, embodies the nascent individual: unformed, not yet integrated into the broader moral order, animated but incomplete—much like a human child who enters the world full of potential but lacking structure and discernment.

Geppetto, as the father figure, is not merely a carpenter tinkering with a block of wood; he is the archetypal paternal presence, the craftsman of culture, imbuing raw matter with form and possibility. In many respects, this dynamic echoes the relationship between tradition and the individual. A child, like Pinocchio, initially receives its shape and orientation from the father—both literal and symbolic—who provides the rough scaffolding for future moral and psychological development.

The Nose as Moral Barometer: Truth and Its Consequences

Yet Pinocchio is not just an innocent tabula rasa. He carries within him the seeds of moral failing and deceit, symbolized most starkly by his ever-growing nose each time he tells a lie. This is not a trivial physical anomaly; it’s a psychological and spiritual truth manifested in fairy-tale form.

The elongation of the nose represents the visible evidence of moral error. In a world where truth and authenticity are the bedrock of meaningful existence, the lie is not merely a misstatement; it corrupts the integrity of the individual. We can see this as a commentary on the ethical and psychological dangers of falsehood: Each untruth we utter subtly reshapes our character, twisting and contorting our being until we can no longer hide the deformities of our soul. Pinocchio’s nose is the warning sign that no untruth remains inconsequential. In the symbolic universe, the structure of morality is built so that the damage of lying reverberates through the psyche, eventually making itself apparent—often painfully so.

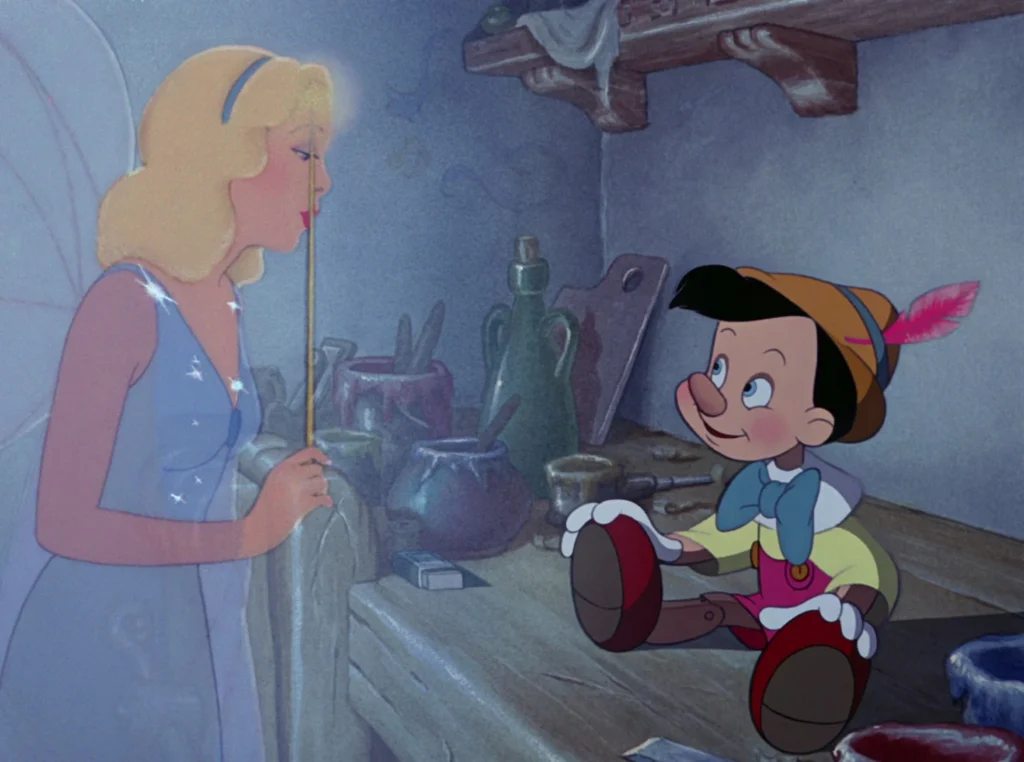

The Blue Fairy: An Archetype of Nurturing Wisdom

The Blue Fairy, or the shimmering feminine figure who guides Pinocchio, can be seen as the embodiment of wisdom, grace, and transcendent order. She represents the archetype of the nurturing, truth-bearing feminine—a divine mediator who calls Pinocchio forth out of his wooden limitations.

Through her guidance, we observe the necessity of engaging with forces outside our immediate comprehension. The Blue Fairy is an anima figure, embodying sensitivity, insight, and moral clarity, urging Pinocchio not to remain a puppet but to strive toward becoming a fully realized human being. The interplay between the masculine (Geppetto’s craftsmanship and the paternal order) and the feminine (the Fairy’s guidance and moral correction) sets the conditions for the stable development of character and identity.

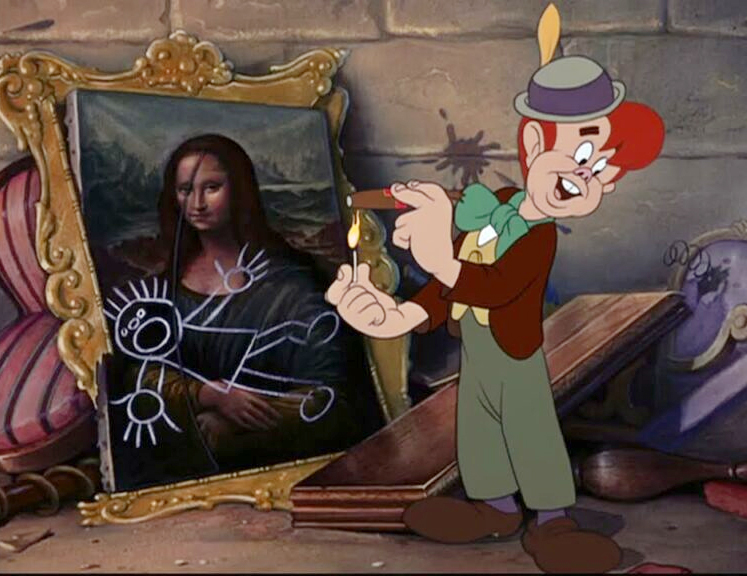

Trials and Temptations: Foxes, Cats, and Pleasure Island

Consider the trials Pinocchio faces, such as his encounters with the cunning fox and cat, and his disastrous sojourn to Pleasure Island. These ordeals represent the temptations that lead a young soul astray: laziness, dishonesty, self-indulgence, and the refusal to confront the demands of responsibility.

Pleasure Island, in particular, is a potent symbol. It’s the place where children, free from adult supervision, can do whatever they wish—eating sweets, breaking rules, indulging in heedless entertainment. But this apparent paradise is no utopia; it’s a trap that distorts the human spirit.

The boys, including Pinocchio, start turning into donkeys—dumb, servile beasts—indicative of what happens when one abandons reason, virtue, and forward-looking discipline in favor of immediate gratification.

The donkey transformation is the ultimate regression into a state of brute nature, a warning about the degenerative consequences of irresponsible freedom. Without guiding principles and moral constraints, one becomes less than human, locked in a cycle of servitude to baser instincts.

Descent into the Whale: Confronting Chaos and Emerging Renewed

A crucial psychological dimension appears when Pinocchio must descend into the whale’s belly to rescue his father. This is a classic “belly of the whale” archetype echoed in countless myths from Jonah to the stories of hero’s quests; representing the transformative journey into the unknown, the chaotic depths.

The whale’s interior is a dark, confining place, reminiscent of the inner chasms of the psyche. It is there, in the encounter with the monstrous and the primal, that Pinocchio comes to understand the value of paternal order, loyalty, and sacrifice. Rescuing Geppetto is not merely a physical liberation; it’s the symbolic reinstatement of right order in Pinocchio’s psyche.

He confronts chaos, takes on responsibility, and emerges from the depths changed, ready to embody the principles of truth, honesty, and moral action.

Jiminy Cricket: The Voice of Conscience and Moral Integration

No discussion of Pinocchio’s mythic journey would be complete without examining the role of Jiminy Cricket, who stands as a vivid personification of conscience. He is not simply a cheerful companion or moral advisor, but a manifestation of the internal voice that seeks to guide individuals toward ethical behavior. Jiminy’s role underscores one of Carl Jung’s central insights: the need to integrate the unconscious forces of morality within the psyche. Without such a voice, the individual is left adrift, unable to discern right from wrong amidst the chaos of existence.

Jiminy does not make decisions for Pinocchio; rather, he advises and warns, embodying the internal struggle between impulsive desires and higher-order aspirations. He represents the necessity of conscious moral engagement, a call to pause, reflect, and act in accordance with principles rather than fleeting whims. His role is not to chastise endlessly but to act as a subtle compass, reminding us of the path toward truth, even when we’re tempted to stray into the forests of deceit or the illusions of Pleasure Island. Jiminy, though small and seemingly insignificant, carries immense symbolic weight. He illustrates that moral guidance comes not from overpowering external authority but from the quiet, persistent voice within—a voice we are free to ignore at our peril.

The Ultimate Transformation: From Wood to Flesh

At the narrative’s culmination, when Pinocchio finally transforms from a wooden puppet into a real human boy, we witness the ultimate psychological and moral metamorphosis. This is the hero’s reward after the confrontation with chaos and error. By facing hardship, acknowledging wrongdoing, striving toward honesty, and risking himself to save his father, Pinocchio internalizes the moral law.

He relinquishes the puppet strings of childish impulses and becomes an agent of his own destiny, fortified by truth and guided by conscience. The shift from wood to flesh symbolizes not merely the attainment of organic life, but the realization of potential into actuality—an ethical and psychological “coming into being.”

Pinocchio’s Lesson for All: Becoming Truly Real

Ultimately, the story of Pinocchio is a profound illustration of the universal struggle to transform raw potential and chaotic impulses into integrated, upright individuality. It teaches that telling the truth, aspiring nobly, and assuming the responsibilities that life inevitably imposes lead to genuine personhood. Far from a simplistic children’s tale, it is a complex, multi-layered narrative depicting the forging of character, the critical role of mentorship and moral guidance, and the heroic necessity of encountering and overcoming the chaos lurking beneath the veneer of civilized order.

In essence, Pinocchio is about becoming real—truly real—in a world where it is far easier to remain wooden and false. It beckons us, with archetypal clarity, to stand up straight and face the world honestly, to rescue what we hold dear from the belly of the beast, and in so doing, carve ourselves into genuine human beings who can walk upright in truth, light, and moral responsibility.

More from Philosophy

Juvenoia: Why Complaining About Youth Is a 2,000-Year-Old Trend

Are Kids These Days Really Worse? We've all seen this before! A teenager walks down the street so immersed on the …

Jesus Christ: History’s Greatest Illusionist?

History tells us that there are not many people who have been able to capture the human imagination. For two thousand …

Inside the Mind of a Magician: The 10 Theories of Magic That Control What You See

Let’s dispense with the obvious. Magic isn’t about wands, rabbits, or children’s parties with balloon swords. It’s not about the suspenders, …