History tells us that there are not many people who have been able to capture the human imagination.

For two thousand years, one man’s reported miracles have been the basis of the Christian faith: walking on water, turning water into wine, multiplying loaves and fishes, healing the sick, and raising the dead. What if we were to re-imagine these feats in a different light? What if the miracle worker of Galilee was really the world’s most talented illusionist of the ancient times? His tricks were so far advanced for their times that people attributed them to a miracle.

Here’s an interesting thought experiment that requires neither faith nor disbelief but merely curiosity. Could Jesus Christ have been history’s greatest magician?

Magic in the Ancient World: The Historical Context

First, before analyzing individual miracles, we must set the scene of Jesus’s time. During the first century a.d., wonder-workers, magicians, mystics, and false prophets were plentiful in the Mediterranean world. In ancient times magical practices existed on a spectrum with religion where genuine magicians did not regard themselves as con men.

The Greek magical papyri of the time exhibit clever tricks for illusions. Egyptian priests were performing miracles for years using natural stuff and tricky mechanisms. The audience was mesmerized during the Eleusinian mysteries by dramatic changes and visions. These illusions often blurred the line between reality and illusion, leaving spectators in awe of the seemingly divine power on display. Behind these spectacles lay an intricate understanding of psychology and perception, capturing a glimpse into the inner workings of belief and wonder. Indeed, peering inside the mind of a magician reveals a deep appreciation for the art of deception and the manipulation of perception, transforming the ordinary into the extraordinary for their enchanted audience.

Fortunately, a performer like Jesus could have worked within the magician’s tradition of performance. A skilled illusionist with high knowledge of the natural sciences and good knowledge of psychology and theatrical presentation could easily achieve such legendary status. In fact, his notoriety would be greatly enhanced if his performances came with deep moral teachings which appealed to the oppressed masses of Roman Judea.

Water into Wine: Chemistry or Sleight of Hand?

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Story

The event takes place in John 2:1–11, at a wedding in Cana of Galilee. Jesus is present at the wedding along with his mother, Mary, and his disciples. During the celebration, the wine runs out. Mary informs Jesus of the issue, saying, “They have no more wine.”

Jesus replies, “Woman, what does this have to do with me? My hour has not yet come.” Nevertheless, Mary tells the servants, “Do whatever he tells you.”

Jesus instructs the servants to fill six stone water jars, each capable of holding 20 to 30 gallons, with water. Once filled to the brim, he tells them to draw some out and take it to the master of the banquet.

When the banquet master tastes it, the water has become wine, and not ordinary wine, but high-quality wine. Surprised, the banquet master calls the bridegroom and remarks that most people serve the best wine first and save the cheaper wine for later, but in this case, the best wine has been saved for last.

This is identified in the Gospel as Jesus’s first recorded miracle, and it takes place privately, without a public announcement or display.

At a wedding ceremony, Jesus commands the servants to fill six massive stone jars with water, it suddenly turns into high-quality wine! From a magician’s point of view, many have suggested this with ancient chemical explanations, natural dyes, plant extracts, pH tricks and so on.

The issue with that is someone tasted it. Not just anyone, the master of the banquet who had to recognize good wine! He didn’t just nod politely; he was impressed. That rules out any basic dye or visual trick.

If this was an illusion, it had to be far more advanced. Modern-day magicians use fake bags, false bottoms, and controlled serving methods. It’s possible the stone jars had a secret compartment for pre-filled wine, probably with unsuspecting servants pulling the right one. Maybe the ladles or jugs used were pre-filled the whole time, making it seem like wine was coming from the jars.

This is typical misdirection, nothing flashy, no attention focused on the moment. Just quiet instructions, and a surprising result. If it was a trick, it wasn’t chemical; it was psychological and masterfully done.

Walking on Water: Optical Illusion and Natural Physics

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Story

The story is recorded in Matthew 14:22–33, Mark 6:45–52, and John 6:16–21. After feeding the five thousand, Jesus sends his disciples ahead of him by boat to cross the Sea of Galilee, while he remains behind alone to pray.

As night falls, a strong wind arises, and the disciples struggle to row against the waves. In the fourth watch of the night (between 3:00 and 6:00 a.m.), they see a figure walking toward them on the water. They are frightened and believe it is a ghost.

Jesus immediately calls out to them, saying, “Take heart; it is I. Do not be afraid.”

According to Matthew’s account, Peter responds by asking Jesus to command him to come out onto the water. Jesus agrees. Peter steps out of the boat and begins walking on the water toward Jesus. But when he notices the wind and becomes afraid, he begins to sink and cries out, “Lord, save me!” Jesus immediately reaches out his hand and catches him, saying, “You of little faith, why did you doubt?”

When Jesus and Peter return to the boat, the wind stops. In Matthew, the disciples in the boat worship Jesus, saying, “Truly you are the Son of God.” In Mark’s version, they are described as completely amazed, but no worship is mentioned.

In all accounts, the incident ends with the boat reaching land safely.

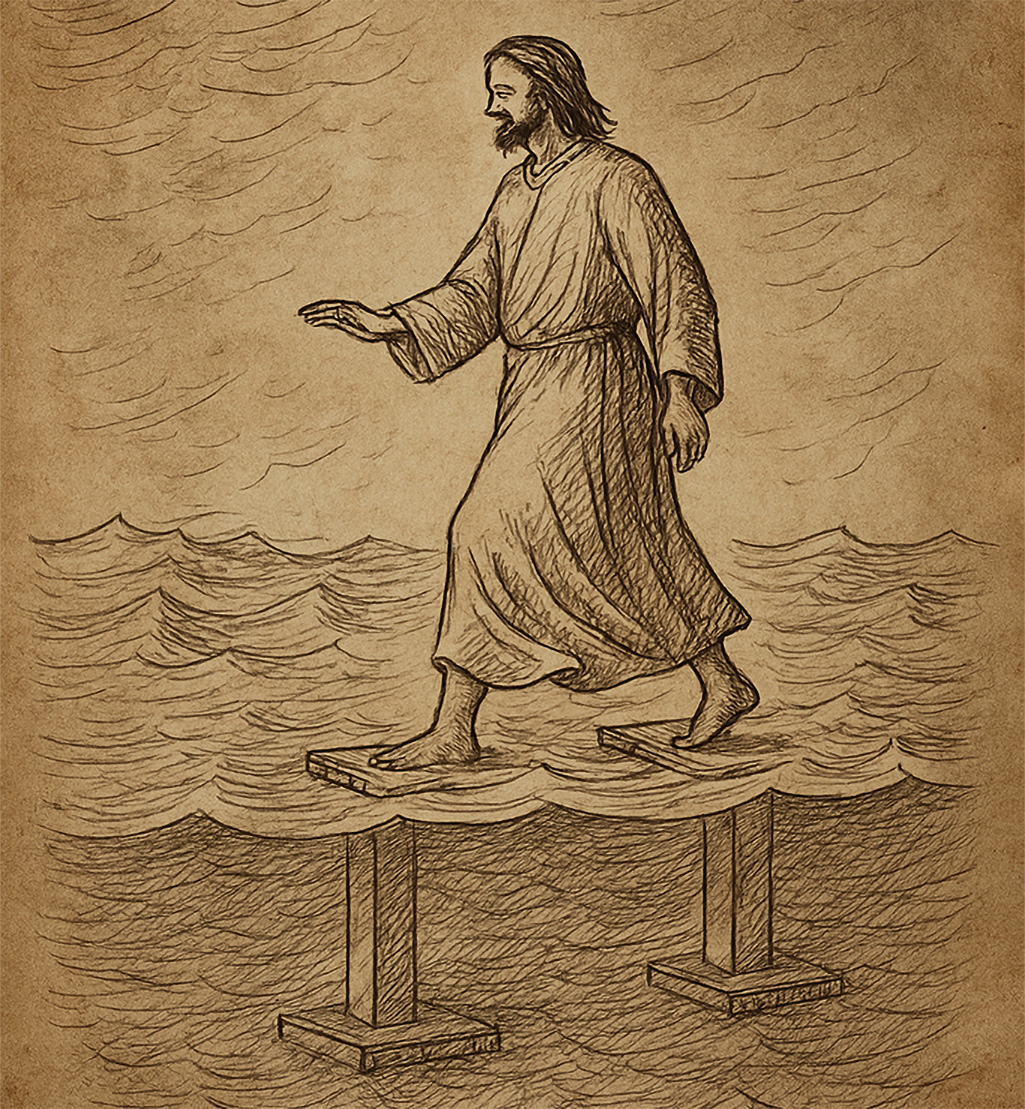

So, a man walking on water is either a god or a trick. In modern times, magicians have done this using Plexiglas submerged just below the surface. If it was the latter, it wasn’t crude. It was deliberate. We’re told it happened between three and six a.m., during a raging storm—dark skies, high winds, rough waters. Conditions that make performing harder, but fooling people easier.

These were experienced fishermen. They knew the lake. The story places them in deep water, not splashing through puddles.

If this was a trick, it needed something like a submerged path in planks or stones laid out in advance. In those stormy conditions, no one would see them. Jesus would only need to cross a short distance to be seen. Just enough to be believed.

Then there’s Peter. He tries to follow and sinks. Was it because his faith failed, or because he didn’t know where to place his foot? This guy doesn’t walk on water. He sinks in it. But according to the text, he also walks for a moment. That throws a spanner in the works. If this were an illusion requiring precise steps, how did Peter manage a few?

That inconsistency muddies the water, so to speak. It could suggest the limits of a staged effect or the natural evolution of a story passed down orally for decades before it was written. Memory isn’t a recorder. It’s an editor. Awe distorts, wonder refines. The amazing gets polished. The rough edges, smoothed out.

It’s a moment both understandable and not. Too theatrical to ignore, too layered to unpack. A paradox never meant to be solved, only remembered. Whatever side you’re on, one thing is certain: those who saw it never forgot.

Coin in the Fish’s Mouth: Baited Coin or Sleight of Hand?

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Story

In Matthew 17:24–27, Jesus and his disciples arrive in Capernaum. Local tax collectors approach Peter and ask whether Jesus pays the two-drachma temple tax, a levy traditionally collected from Jewish men for the upkeep of the temple.

Peter replies, “Yes,” and enters the house where Jesus is staying. Before Peter can say anything, Jesus initiates the conversation, asking, “What do you think, Simon? From whom do the kings of the earth collect duty and taxes, from their own children or from others?” Peter answers, “From others.” Jesus responds, “Then the children are exempt.”

Despite this, Jesus tells Peter to avoid offending the tax collectors. He instructs Peter to go to the lake, cast a line, and catch a fish. Jesus says that in the mouth of the first fish Peter catches, he will find a four-drachma coin, enough to cover the tax for both of them.

The story ends without describing the moment Peter finds the coin, it is implied that the event happens exactly as Jesus predicted.

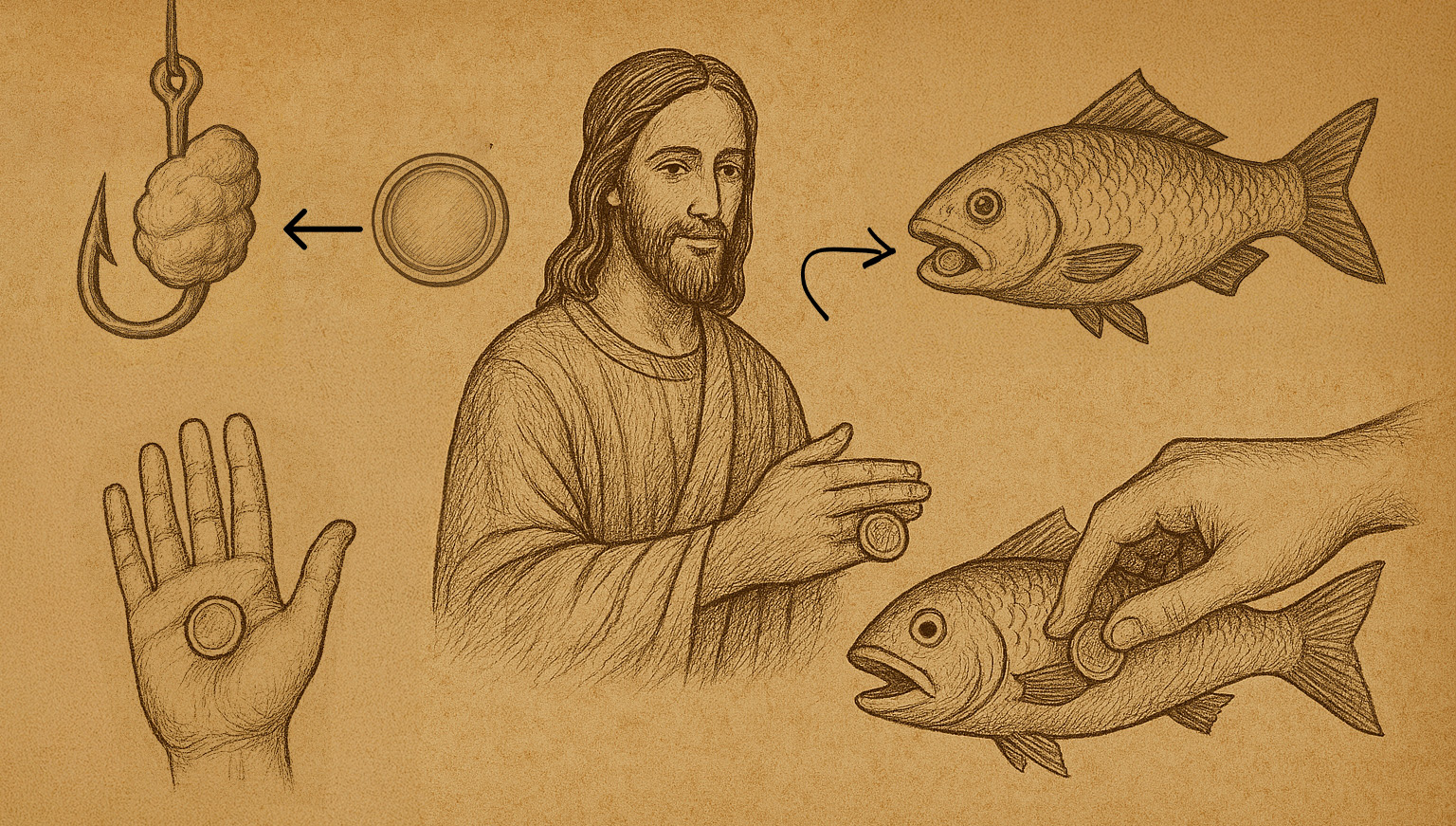

At first glance, it’s a minor miracle. No thunderous declarations, no multitudes fed or raised from the dead. Just Jesus telling Peter to cast a line, and inside the mouth of the first fish he catches was the precise coin needed to pay the temple tax. Modest in scale, yes, but potent in implication. Because unlike the public spectacles, this one is quiet, private, and perfect for close-up magic.

Let’s consider the first possibility: the bait itself was rigged.

Jesus could have prepped a piece of bait containing a coin, let’s say, wrapped in lamb fat or packed into a lump of fermented mash irresistible to local fish. He hands it to Peter with specific instructions and sends him off. The first fish to bite swallows both bait and coin. Peter catches it, cleans it, and finds the surprise. The trick, if it is one, is shockingly simple: one point of preparation, no accomplices, no need for Jesus to be present at all. Like any great illusion, it uses the most powerful ingredient of all to hide its mechanics in plain sight.

But now we turn to the second theory. Entirely unrelated, and arguably more elegant. This version depends not on bait but on presence. The Gospel doesn’t specify whether Jesus accompanied Peter to the water, it merely tells us he gave the instruction. But suppose he did go with him.

Peter casts the line, gets a bite, hauls in a fish. Jesus, standing beside him, steps forward naturally. “Let me hold it while you take out the hook,” he might say; an offer that seems helpful, even fatherly. And in that brief, unsuspicious moment, Jesus takes the fish in hand. What happens next is textbook sleight of hand: a palmed coin, slipped expertly into the fish’s mouth or gill cavity, concealed from view by nothing more than timing and trust.

Peter, of course, is focused on the line or the hook, he’s not watching for a trick. Why would he be? The “miracle” has already been predicted. The only job now is to discover it.

And that’s precisely the point. The psychological power of this moment lies not in the reveal, but in the expectation. Jesus doesn’t just find a coin. He says a coin will be found; before the catch, before the fish, before the coin even enters the scene. The moment he handles the fish is a blur, an afterthought. What Peter will remember isn’t the logistics, it’s the prophecy come true.

Modern mentalists rely on this exact principle: manipulate perception before the climax, and when the outcome arrives, the audience convinces itself of the miracle. Derren Brown does it. So did Houdini. The genius isn’t in the trick, it’s in making people forget the setup.

The act lasts seconds. The result, however, is far more lasting: a fulfilled prophecy, an astonished disciple, and a story that will be passed down for generations. So, was it divine foresight or manual finesse? Perhaps we’ll never know. But if it was an illusion, it wasn’t cheap theatre, it was the kind of performance that reshapes belief. No props, no platform, just one man, one fish, and one moment of perfectly executed wonder.

The Clay Birds: Misdirection and Concealment

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Story

In the Infancy Gospel of Thomas (chapter 2), Jesus is described as a young child, around five years old, playing near a stream on the Sabbath. Using the soft clay from the water, he molds twelve sparrows. This act catches the attention of a Jewish onlooker, who is offended by what he perceives as Jesus violating the Sabbath by "working" with clay. He rushes to tell Joseph.

Before Joseph can intervene, Jesus responds to the accusation. Standing over the clay birds, he claps his hands and commands them, saying, “Go!” Instantly, the twelve clay birds come to life and fly off chirping into the sky.

The miracle, as told in the text, is both a response to criticism and a demonstration of divine power, emphasizing Jesus’ supernatural abilities even as a child. While not included in the canonical gospels, this story was widely circulated in early Christian communities and offers a glimpse into how some early believers imagined Jesus’s youth, as both miraculous and confrontational.

In the Infancy Gospel of Thomas, an apocryphal text where young Jesus veers from precocious to mildly terrifying we find a curious tale. On the Sabbath, he molds twelve clay birds by a stream. A pious onlooker cries foul. Jesus claps his hands and the birds fly off.

Let’s sidestep the theological implications of divine tantrums and ask something juicier: was this miracle… a performance?

Picture Jesus not as an innocent child with divine instinct, but as a shrewd showman. Magicians today like Copperfield and Blaine, make birds appear from nowhere using sleight-of-hand, concealment, and impeccable timing. No sorcery, just skill.

Now rewind to first-century Judea. A boy from a carpenter’s household would know how to craft concealment: wicker, cloth, straw. Tame birds, sparrows, and doves were common. With a bit of cunning, a hidden pouch under a cloak or beside him in the dust could easily hold the secret.

He sculpts the clay birds by the stream. The real birds wait nearby, silent. The setup is casual: a child playing in the mud. Then the rebuke comes: “Sabbath violation!” Cue the reveal. Jesus claps. With a flick or pull, the birds are loosed. They soar. Feathers catch the light.

And here’s the brilliance: no one sees the pouch. They see clay, a boy, then flight. The mind fills in the rest. The illusion lands because the story does. This wasn’t reaction, it was orchestration. Not divine fury, but controlled drama. Creation, animation, and awe, all in one gesture. So was it a spark of the divine? Maybe. But it could just as easily have been the earliest dove act performed not for spectacle, but to command perception.

Because the real trick isn’t in the hands. It’s in the mind.

Prophecy as Psychology: The Power of Perception and Memory

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Stories

1. Peter’s Denial

In Luke 22:34, Jesus tells Peter that he will deny knowing him three times before the rooster crows the next morning. Despite Peter’s insistence that he would never do so, the prediction comes true later that night when Peter, out of fear, denies being associated with Jesus while warming himself by a fire during Jesus’ trial.

2. Judas’s Betrayal

In Matthew 26:21–25, during the Last Supper, Jesus announces that one of the twelve disciples will betray him. The group is shocked, and each asks if it is them. Jesus gives a vague but pointed reply. Judas also asks, and Jesus confirms it subtly. Shortly after, Judas leaves to carry out the betrayal.

3. Destruction of the Temple

In Matthew 24:1–2, as the disciples admire the grandeur of the Jerusalem Temple, Jesus tells them that the time will come when not one stone will be left on another. Roughly four decades later, the temple is completely destroyed by the Romans during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Throughout the gospels, Jesus makes a series of eerily accurate predictions, Peter’s denial before the rooster crows (Luke 22:34), Judas’s betrayal at the Last Supper (Matthew 26:21–25), and the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple (Matthew 24:1–2). These are framed as divine foresight. But through another lens, they look more like educated guesses; all made with impeccable timing, delivered with confidence, and later remembered as miracles.

Take Peter. Emotional, impulsive, and visibly shaken, he insists he’ll never disown Jesus. But Jesus knows fear when he sees it. Predicting Peter will crumble under pressure isn’t prophecy, it’s psychology. The rooster detail? A mental anchor. When it happens, it hits like thunder. Peter breaks. The moment becomes legend.

At the Last Supper, Jesus warns someone will betray him. No name and no theatrics, just a vague line dropped into a charged atmosphere. If nothing happens, it fades. But if someone does turn, the memory reconfigures. Judas, already uneasy, walks into the role like it was written for him.

The Temple prediction sounds grander but remains rooted in context. Political tension with Rome was rising. Revolt was in the air. For someone attuned to the moment, forecasting collapse wasn’t divine, it was probable. When the Temple fell in 70 CE, Jesus’s words resurfaced, repackaged as prophecy.

And that’s the genius. Like any seasoned mentalist, Jesus knew the power of timing, ambiguity, and memory. Say ten things and two come true, those two are canon. Vague phrasing lets memory do the work. And once belief kicks in, the audience completes the illusion.

So were these divine insights? Possibly. But they also follow the oldest rule in the magician’s playbook: control the setup, and the reveal will follow. Because real miracle-workers don’t need to command the future, only the way we remember the present.

The Resurrection: A Masterclass in Controlled Perception

Expand to Read a Summary of the Biblical Story

According to all four canonical Gospels, Jesus is crucified and buried in a rock-cut tomb, provided by Joseph of Arimathea. A large stone is placed at the entrance. On the third day after his death, several women, including Mary Magdalene, visit the tomb and find the stone rolled away and the tomb empty.

In Matthew, an angel appears and tells them Jesus has risen. In John, Mary Magdalene sees Jesus outside the tomb but does not recognize him at first. In Luke and Mark, other followers are told by angels that Jesus has risen and will appear to the disciples.

Over the next days, Jesus appears to various followers: to Mary Magdalene, to two disciples on the road to Emmaus, to the disciples in a locked room, and later to Thomas, who doubts until he sees the wounds. In Matthew, Jesus meets them in Galilee and gives final instructions.

The Gospels agree that Jesus’s body disappears from the tomb and that his followers claim to have seen him alive, though the details of these encounters vary between accounts.

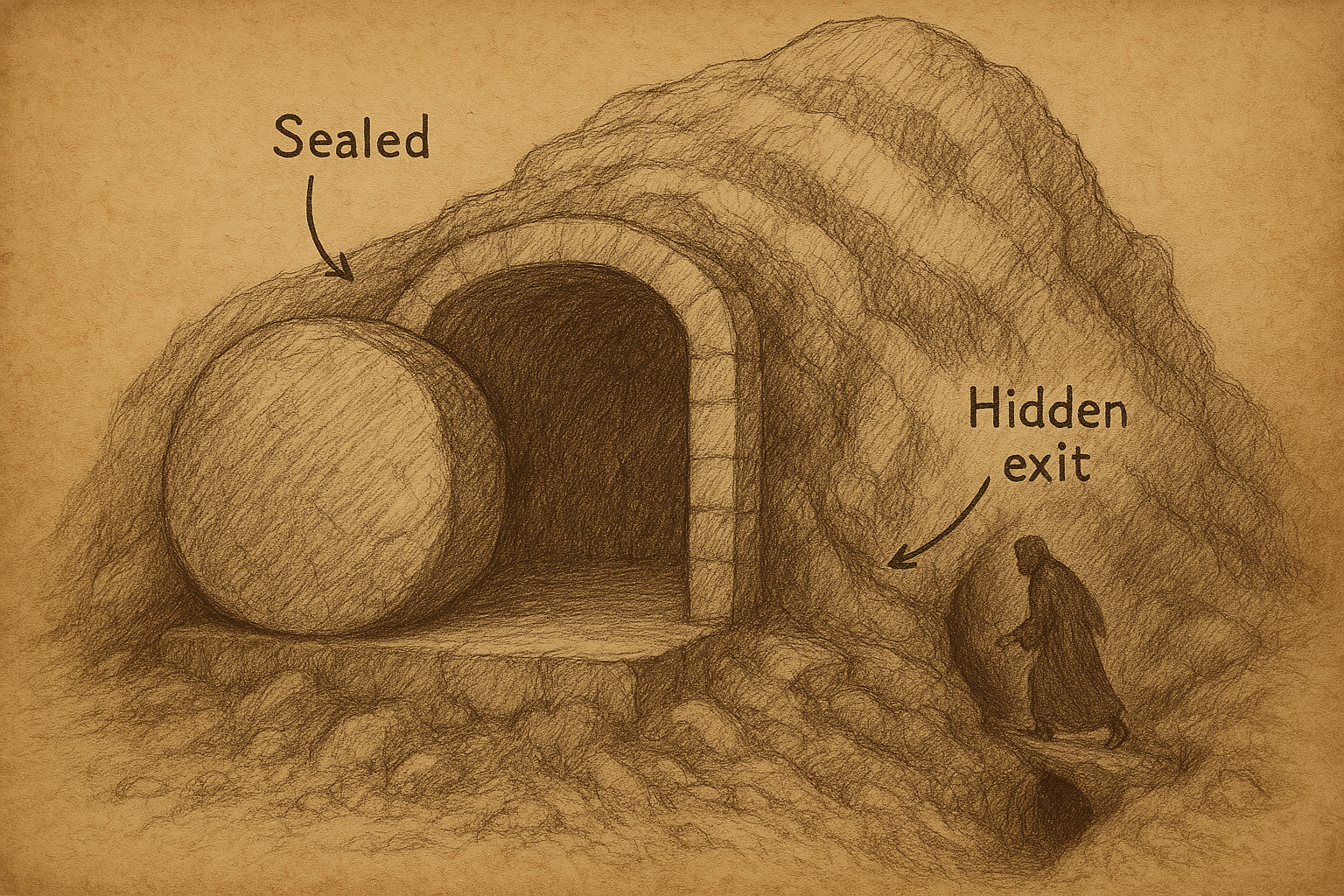

Of all Jesus’s miracles, the resurrection is the centerpiece. Not just spiritually, but narratively. It’s the pivot point, viewed not as divine intervention, but as illusion. Or something carefully planned and presented, it begins to resemble masterful stagecraft.

First, the wounds. When Jesus shows up, he shows the disciples his pierced hands and wounded side. To the faithful, this proves identity. But it’s a classic from the performer’s playbook, which is continuity that sells the trick. An audience member could see a visible injury and say, “This must be the same man.” But what if it wasn’t? A prepared double with similar wounds, or even a misidentified body in the tomb, could achieve the same effect. The wounds don’t settle the question, they complicate it.

Then the tomb itself. Joseph of Arimathea, a follower, claims the body and places it in his own rock-hewn chamber—not a public grave, but a private, controlled setting. The stone blocking the entrance is described as so heavy that the women ask each other who will roll the stone away from the entrance of the tomb (Mark 16:3). This detail heightens the sense of finality. It’s the magician’s locked box: once sealed, the audience assumes no exit is possible.

What the Gospels don’t elaborate on is the tomb’s interior. Many such chambers included side shafts, drainage holes, or service passages. If one existed, it would be known only to Joseph and Jesus. Jesus enters, and when night falls, he leaves through another way. The front stone stays in place until it’s dramatically moved.

According to Matthew 28:2, only the guards witnessed an earthquake and an angel rolling the stone away. To some, divine intervention. To others, narrative flourish. A prearranged team could have moved it with perfect timing. Crucially, no one sees Jesus leave. The audience sees only the aftermath. The empty tomb is the reveal. The trick happens offstage.

His future reappearances follow the same principle: short, personal, visceral. Always to individuals or small groups. and never to crowds. Never in broad daylight and often unrecognized. These aren’t public demonstrations, but rather private encounters carefully crafted for individuals who are already believers.

The Psychology of Miracle and Memory

Memory does not work like a camera. It doesn’t record, it reconstructs. When linked to an emotion, such as fear, hope, or awe, memory becomes flexible, creative, and, often, unreliable. The brain doesn’t care to be accurate; it cares to make meaning. That’s why miracles, as remembered, don’t survive because they were exactly right, but because they struck a chord. A woman supposedly healed by a piece of cloth might not get better medically but something happened to her. And that change became her truth. Over time, repetition polishes these stories into gleaming gems, their luster shaped by retelling.eir shining gloss brought on by the repetition.

And so we must consider the context. Historians did not capture these miracles in real-time. The stories were saved by those who believed, who remembered through faith, and who shared their stories through a remembering oral tradition over the decades. This doesn’t make them false, but it does make them human. The miracles exist not because they’re provable but because they provide hope. They converse with our connection and offer us a legitimate conviction, that one may have the ability to influence reality by focusing on something acutely enough.

The Mind Behind the Myth

Let’s turn back the clock to the thought experiment: let us suppose Jesus of Nazareth was not divine, and the miracles were no more than supernatural. Think of a man who’s bright, intuitive, and a master of belief. A proto-psychologist. A strategist. A performer not of mere illusions, but of powerful ideas.

He gathered the masses, provoked the elite, and instigated a movement that survived empires, all without institutions, media, or wealth. Without the miracle, it is even more impressive. Everything wasn’t for display. Everything was for change. Not to trick, but to teach

Perhaps the coin in the fish was planted. Maybe the clay birds were swapped with real ones. Or the tomb had another exit. That doesn’t require fraud, just time, belief, and human hunger for meaning. Even if the miracles weren’t real, they weren’t empty. They carried purpose and they provided hope. They created a narrative that defined what we now call civilization.

And here’s the uncomfortable truth we don’t like to admit: most of us would rather follow a compelling fiction than a dull fact. A man who can cure the blind will be more effective than one who just gives a good lecture. Myth is sticky, as it binds people in a way data never can. Maybe Jesus knew that, and maybe he used it to communicate something more than truth. His own vision.

And that’s the paradox. If Jesus was divine, the miracles proved it. But if he was just a man? Then he achieved what emperors and philosophers never could. He changed the world through meaning alone. Not violence, not wealth, just words and moments.

Final Act: The Illusion That Became Reality

So perhaps it wasn’t water into wine, or death into life. Perhaps it was fear into hope. Doubt into belief. A clever trick into an enduring myth.

But if Jesus was merely a man armed with foresight, timing, and the ability to shape perception, then the real marvel isn’t that people were fooled. It’s that they remained transformed. His acts didn’t just astonish. They organized communities, inspired revolutions, and seeded a moral framework that still shapes how we treat strangers, power, and pain.

Magicians usually vanish when the curtain falls. Jesus didn’t. The story endured not because it defied nature, but because it aligned with something deeper in us: the need for a story that makes sense of suffering and gives purpose to life.

If that was the trick, it worked. And we’re still clapping.

More from Fun

You Won’t Believe What People Are Googling: Auto-Suggest Nightmares

Without a doubt, Google autocomplete is one of the most illuminating windows into the human psyche. It’s not some cold, …

Seeing Faces in Everyday Objects? Here’s What’s Really Happening

Human cognition is both a marvel and a mystery. It is a tool forged in the fires of evolution, honed …

Can You Tell If This Art Is Human or AI? Most People Can’t!

Once upon a time, art was the way humans flexed, a way to show off our emotions, imagination, and skill. …