To grasp feminism’s current existential crisis, let’s take a walk through its history. Like any movement, feminism has evolved through different waves addressing particular injustices of its day. What began as a focused demand for fundamental equality with men eventually turned into a unruly and often spiteful debate about what feminism really is, about what it should be, and what it has been accused of having become. Let’s unpack this wave by wave.

FIRST WAVE

The Struggle for Basics

1800s to Early 1900s

The first wave of feminism can be looked upon as the foundation. This stage is the least controversial and most focused. It has a kind of tired but true common sense to it and clearly delineated goals. When we think of individuals associated with the first wave, we might picture figures ranging from the Founding Mothers to our no-nonsense grandmothers of a century or so ago.

First-wave feminists are known for demanding the basic human rights, like being recognized by society as human beings with just as much right to live in the public sphere as any man.

What is implied here? Feminism’s first wave was not concerned with dismantling institutions; it was concerned with getting into them. The feminists of this era did not see themselves as in opposition to men but as in league with men in the struggle to make institutions fair to all human beings.

SECOND WAVE

Beyond the Vote to the Bedroom & Workplace

1960s to 1980s

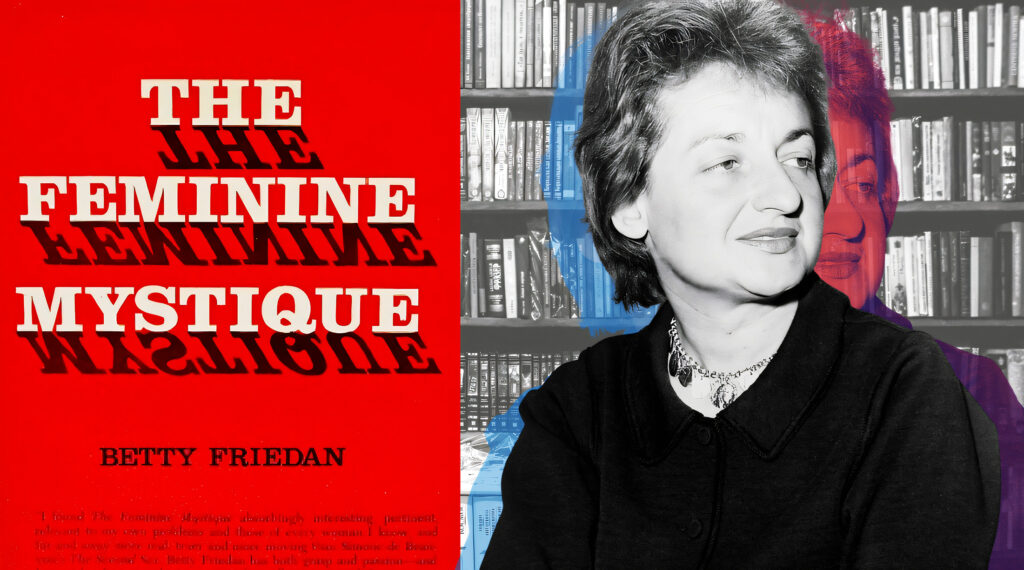

With the right to vote now securely in hand, the second wave of feminism asked, “What’s the point of voting if we’re still second-class citizens in every other way?” It was within this context that Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique, published in 1963, captured the consciousness of women across the country and rendered their long-suppressed grievances into words.

On a very fundamental level, the second wave brought women into the very platforms of society where discussions about their rights could take place: the workplace, the state legislature, and the “conscience of the country“ as Gloria Steinem puts it.

Second-wave feminism was both exhilarating and somewhat excessive. It addressed many serious forms of injustice, but parts of it took on a kind of puritanism that could be pretty cultural.

You know; the kind that uses funny caricatures, think of the “bra-burning” scene, or funny slogans like “a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle,” to make a point. This was a movement that started to polarize pretty dramatically.

THIRD WAVE

Individualism and Intersectionality

1990s to 2000s

The third wave of feminism took form in the 1990s in response to the prescriptive nature of the preceding wave. The defining intellectual framework was intersectionality. This paradigm was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.

To her, intersectionality posed the notion that gender was just one layer of identity and that factors like race, class, and sexuality compounded the experience of being female; whether this is in either a privileged or an oppressed way. It was a groundbreaking idea, and from it emerged a feminism that was much more capacious and much more exciting.

Yet the movement’s growth brought new hurdles to overcome. Feminism’s newfound acceptance of individuality and diversity threatened to water down its aims to the point that it might no longer be able to tackle the systemic inequalities it once challenged.

The third wave was a bold experiment. It was all about rethinking feminism for a more evolved world.

FOURTH WAVE

Digital Activism and Identity Politics

2010s to Present

The fourth wave of American feminism began in the 2010s and is still currently underway. This wave emerged during the rise of social media and digital platforms, where hashtags and viral campaigns became the new tools of activists. The fourth wave is marked by a focus on intersectionality, addressing the diverse experiences of women across different racial, economic, and sexual identities. Activists leverage cancel culture and social media dynamics to hold individuals and organizations accountable for their actions, amplifying voices that were previously marginalized. This wave has also sparked conversations around issues such as sexual harassment, body positivity, and reproductive rights, forging a stronger sense of community and solidarity among feminists worldwide.

The fourth wave’s crown jewel might as well be the #MeToo movement, which stands alongside the powerful 2014 essay by Lauren Berlant that calls for “a feminism of the future.” These platforms allow feminists and activists to converse more publicly with the larger society, to demand a hearing and to make the accusation that society isn’t hearing them when it should. Yet what we see today on these platforms comes off as less serious and revolutionary than the protests of tobacco-spitting soldiers and fire-breathing Suffragettes.

We live in a time of internal contradictions. The fourth wave lauds inclusivity but often silences dissent with terms like “bigot” or “TERF.” It advocates for the voices of marginalized groups but tries to figure out how to make the interests of those groups mesh, especially when the interests of one group conflict with the interests of another. The whole movement now seems to be a microcosm of our larger cultural debates.

When Feminism Goes Against Women

Modern feminism appears to be increasingly contradictory with regard to women’s rights. Feminism has long been recognized as the movement for “the advocacy of women’s rights on the basis of the equality of all the sexes.” the movement has almost universally recognized the scientific fact of biological sex differentiating women from men, which is no longer the case.

Modern feminists now call for the inclusion of self-identified women who are, in fact, biologically male; allowing them in the very same spaces for which feminists have fought for safe passage away from biologically male bodies.

What is worse is that it reduces women to a parody of themselves. Being a woman is neither a costume one can put on nor a feeling one can proclaim; it is a reality that is rooted in a biological condition and lived experience.

1. Trans Women Winning Women’s Competitions

Weightlifting Controversy:

- Laurel Hubbard, a transgender woman, competed in the women’s weightlifting category at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics. Critics argued that biological advantages gave Hubbard an unfair edge over biological women who trained under the same conditions. (source)

Track and Field Dominance:

- Transgender athletes like Terry Miller and Andraya Yearwood dominated high school girls’ track events in Connecticut, sparking lawsuits and debates over fairness in women’s sports. (source)

2. Trans Women Receiving Women’s Honors

Woman of the Year:

- In 2015, Caitlyn Jenner, a transgender woman, was awarded Glamour’s “Woman of the Year” award, drawing backlash from critics who argued that the honor overlooked biological women’s achievements. (source)

Pageant Inclusion:

- In 2018, Angela Ponce became the first transgender woman to compete in the Miss Universe pageant, with some viewing this as a redefinition of womanhood itself. (source)

3. Redefining Women-Only Spaces

Prison Safety Concerns:

- Cases such as transgender inmates being housed in women’s prisons have raised safety issues, including reports of assaults by individuals with male anatomy who identify as women. (source)

Shelter Policies:

- Women’s shelters in some areas have been pressured to admit transgender women, leading to concerns over the safety and comfort of biologically female residents. (source)

4. Policies Affecting Women’s Opportunities

Title IX Changes:

- Efforts to include transgender athletes in women’s sports under Title IX have been criticized for undermining the original intent of providing opportunities for biological women in athletics. (source)

Scholarships and Awards:

- Transgender women competing against biological women have taken scholarships and awards originally intended to support female athletes. (source)

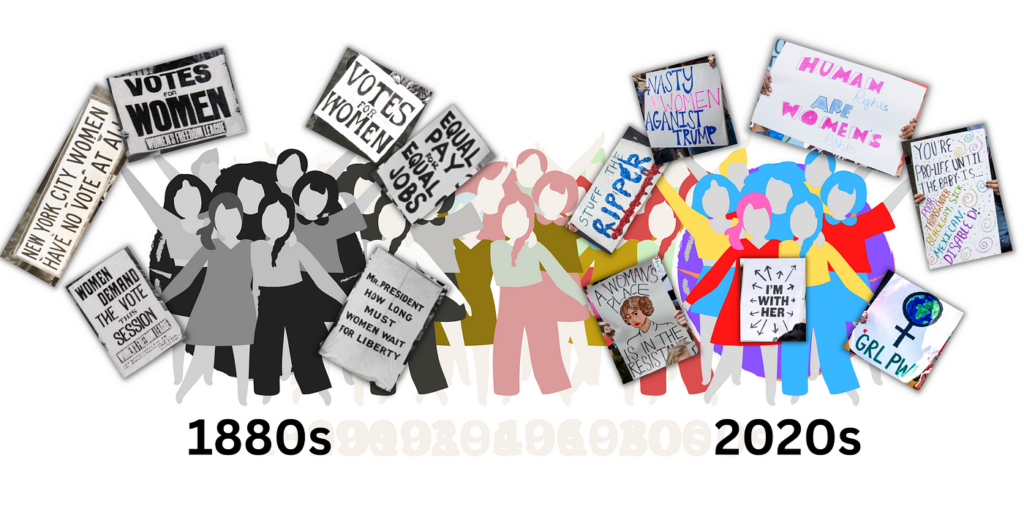

Cultural Tensions & Shades of Feminism

Each wave of feminism has produced its era’s injustices and priorities. However, when you look at first-wave feminism beside fourth-wave feminism, there is a clear cultural shift from pursuing tangible goals to pursuing abstract concepts and causing some cultural tension.

- First-wave feminists were not shy about saying exactly what they wanted. Their demands were straightforward and idealistic but certainly not abstract.

- Second-wave feminists extended the vision of the first wave and embraced the era’s ideals of personal and social transformation; they were still very much rooted in “issues” feminism, though.

- Third-wave feminists blended all of these ideas and embraced some valuable new nuance, but their “intersectional” perspective began to risk clouding the movement’s focus.

And here we are now with the fourth wave, caught in a feedback loop of self-examination finding ourselves in this situation.

Feminism was once a disciplined force for change and a clear force for something that society needed. And now it appears fractured and confused with divide happening in its own party.

It’s a classic case of a movement that has tried to be all things to all people and has surely lost its core identity in attempting to do so.

More from Editor Picks

Seeing Faces in Everyday Objects? Here’s What’s Really Happening

Human cognition is both a marvel and a mystery. It is a tool forged in the fires of evolution, honed …

Cartoon Doppelgängers: When Real Life Takes a Detour to Looney Town

Have you ever walked down the street, looked at someone, and thought, “Wait a minute, why does it look like …

Only 1% Get Every Question Right: Are You One of Them?

This quiz doesn’t care about your GPA, your LinkedIn bio, or your self-esteem 💡 It only cares about right answers …