TLDR: The Hubble and James Webb Space Telescopes work in tandem to reveal the universe’s secrets. Hubble captures visible and ultraviolet light to provide detailed images of galaxies and cosmic phenomena, while Webb explores the universe’s earliest moments and hidden details using infrared. Together, they complement each other, enhancing our understanding of cosmic origins and humanity’s connection to the universe.

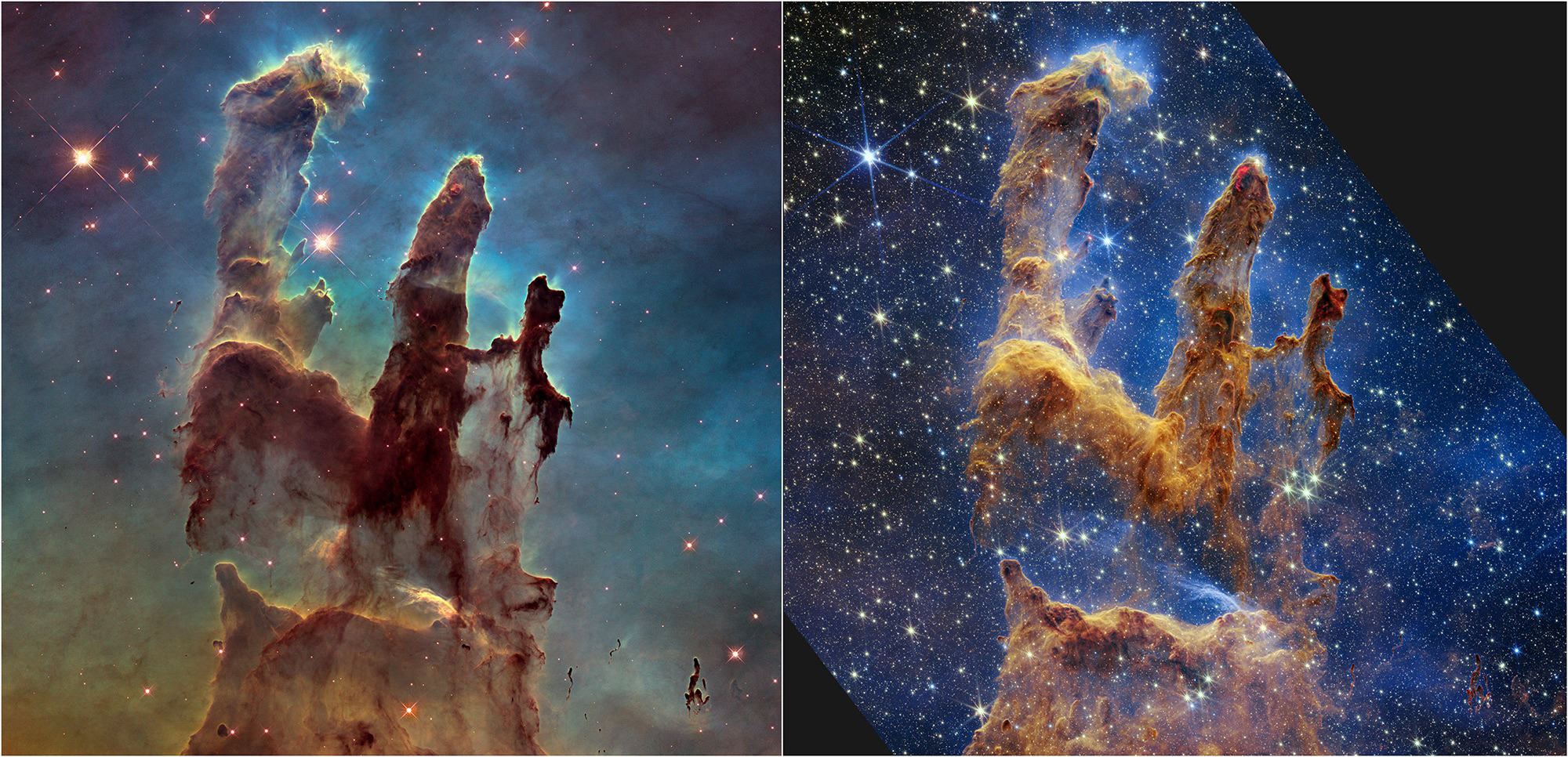

- Hubble specializes in visible and ultraviolet light, offering clear views of nearby and relatively “recent” cosmic phenomena. It avoids Earth’s atmospheric distortions, providing groundbreaking insights into galaxies, star clusters, and iconic formations like the Pillars of Creation.

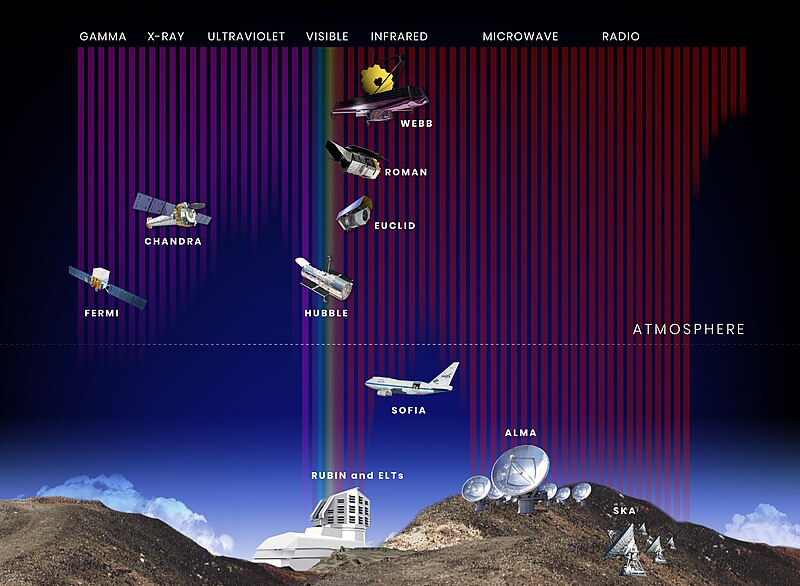

- Webb focuses on infrared light, unveiling early galaxies and star-forming regions hidden by cosmic dust. Its ability to detect faint light from the universe’s infancy and probe the atmospheres of exoplanets marks a new era in cosmic exploration.

- By working together, these telescopes create a comprehensive view of the cosmos. Hubble captures the present, while Webb investigates the distant past, filling gaps in our understanding of how the universe evolved.

- Their discoveries redefine our perspective, showing that the universe is more vast, intricate, and dynamic than imagined, enriching our sense of humanity’s place in the cosmos.

The universe is, in a sense, a faint chorus of distant whispers. Each galaxy, star, and nebula emits an ancient tune of light, a story encoded in electromagnetic waves. But we humans are pretty light-limited.

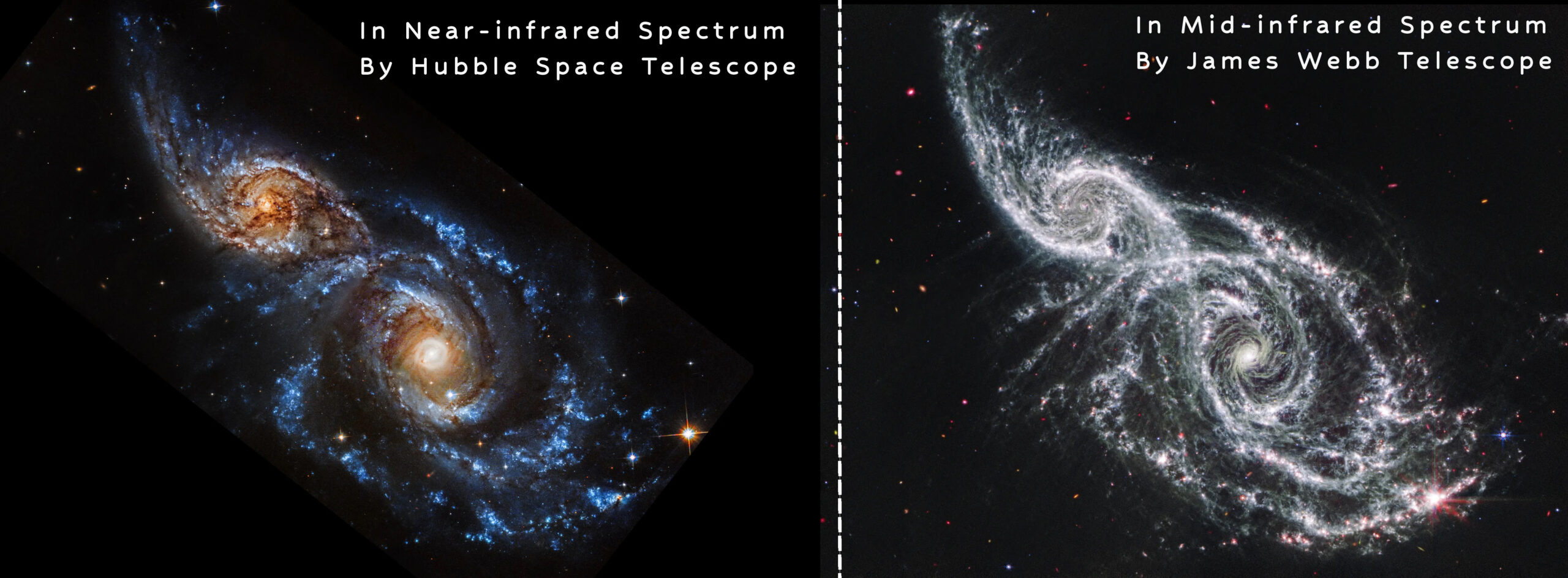

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope made the Pillars of Creation famous with its first image in 1995, but revisited the scene in 2014 to reveal a sharper, wider view in visible light, shown above at left. A new, near-infrared-light view from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, at right, helps us peer through more of the dust in this star-forming region. The thick, dusty brown pillars are no longer as opaque and many more red stars that are still forming come into view.

An artist’s concept of Centaur 29P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 1’s outgassing activity as seen from the side. While prior radio-wavelength observations showed a jet of gas pointed toward Earth, astronomers used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to gather additional insight on the front jet’s composition and noted three more jets of gas spewing from Centaur 29P’s surface.

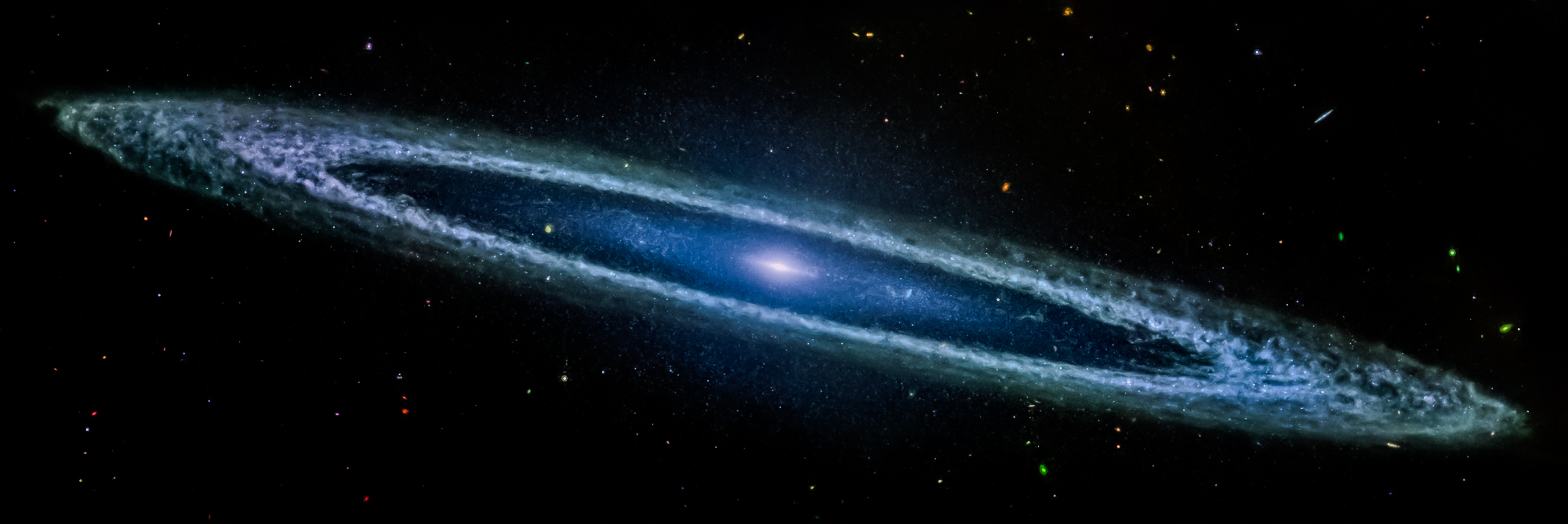

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope recently imaged the Sombrero galaxy with its MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), resolving the clumpy nature of the dust along the galaxy’s outer ring. This image includes filters representing 7.7-micron light as blue, 11.3-micron light as green, and 12.8-micron light as red.

The first anniversary image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope displays star birth like it’s never been seen before, full of detailed, impressionistic texture. The subject is the Rho Ophiuchi cloud complex, the closest star-forming region to Earth. It is a relatively small, quiet stellar nursery, but you’d never know it from Webb’s chaotic close-up. Jets bursting from young stars crisscross the image, impacting the surrounding interstellar gas and lighting up molecular hydrogen, shown in red. Some stars display the telltale shadow of a circumstellar disk, the makings of future planetary systems.

We see only a small slice of the grand electromagnetic buffet. In fact, our eyes are basically instruments optimized to decode a narrow range of wavelengths, much like tuning into a single radio station and ignoring all the others. So, to hear the full cosmic melody, we need telescopes—big, orbiting mechanical eyes that let us tune in to the parts of that cosmic broadcast we’d otherwise miss.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s mid-infrared view of the Pillars of Creation strikes a chilling tone. Thousands of stars that exist in this region seem to disappear, since stars typically do not emit much mid-infrared light, and seemingly endless layers of gas and dust become the centerpiece. The detection of dust by Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) is extremely important – dust is a major ingredient for star formation.

Enter the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope. Both exist to show us what we can’t see with the naked eye, but they do this in very different ways and for very different reasons. It’s a lot like having two translators who are both fluent in “Universe,” but specialize in distinct dialects of that language.

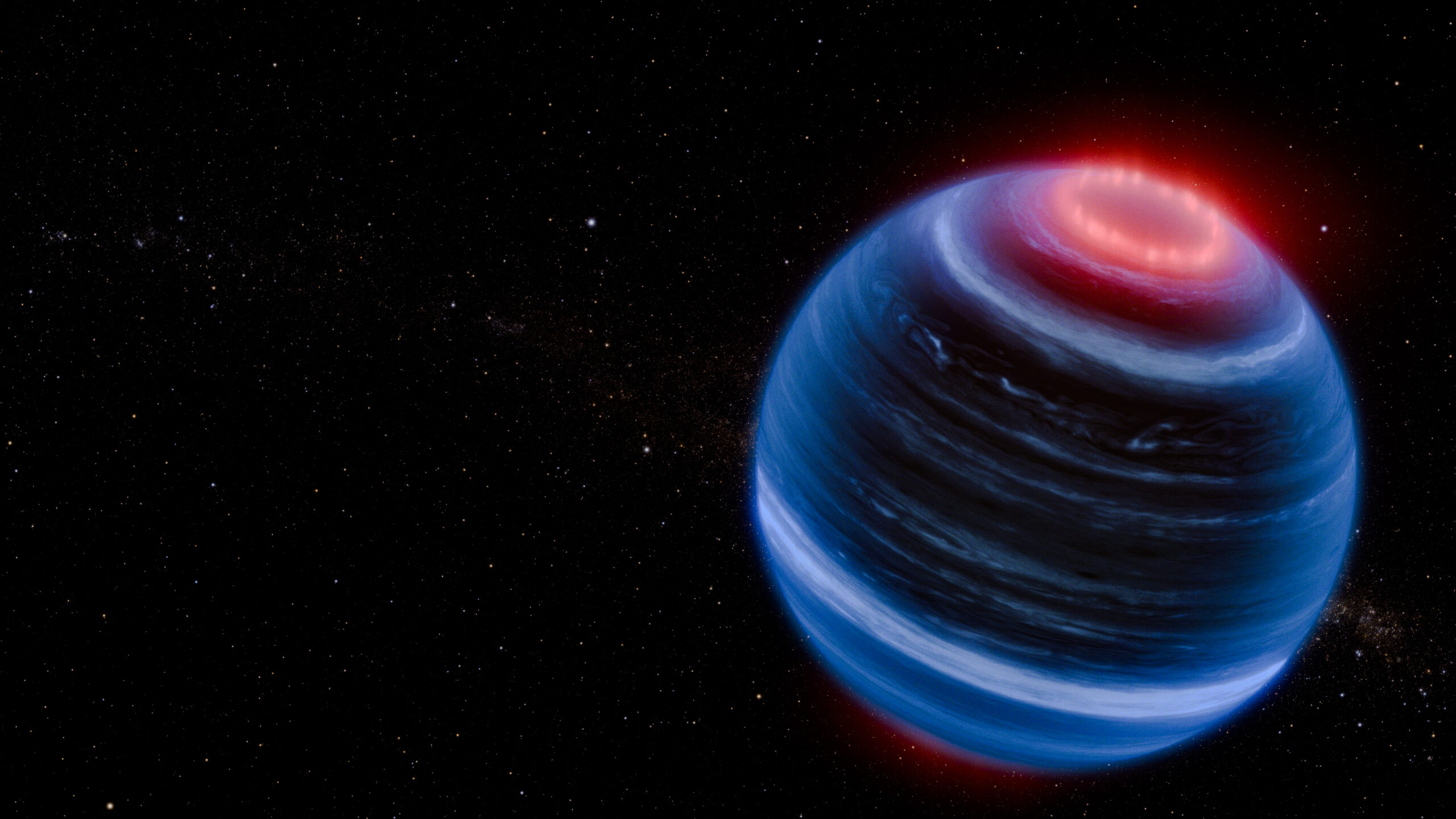

This artist concept portrays the brown dwarf W1935, which is located 47 light-years from Earth. Astronomers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope found infrared emission from methane coming from W1935. This is an unexpected discovery because the brown dwarf is cold and lacks a host star; therefore, there is no obvious source of energy to heat its upper atmosphere and make the methane glow. The team speculates that the methane emission may be due to processes generating aurorae, shown here in red.

Hubble’s forte? Mostly visible and ultraviolet wavelengths—light that’s not too different from what you and I perceive every day. Webb, however, specializes in infrared, which is literally a different dimension of vision, one that can unveil objects so old and far away their light has been stretched and dimmed, rendered completely invisible to ordinary eyes.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope recently imaged the Sombrero galaxy with its MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), resolving the clumpy nature of the dust along the galaxy’s outer ring. This image includes filters representing 7.7-micron light as blue, 11.3-micron light as green, and 12.8-micron light as red.

Let’s start with Hubble. Launched in 1990, it orbits about 540 kilometers above Earth’s surface. Picture it cruising around our planet every 97 minutes, like a perpetual satellite photographer snapping billions-of-years-old candid shots of the cosmos. Before Hubble, ground-based telescopes battled through turbulent layers of atmosphere that blur and distort images.

This mid-infrared image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope excels at showing where the cold dust, set off in white, glows throughout these two galaxies, IC 2163 and NGC 2207. The telescope also helps pinpoint where stars and star clusters are buried within the dust. These regions are bright pink. Some of the pink dots may be extremely distant active supermassive black holes known as quasars.

Imagine trying to read tiny, distant street signs through a wobbly heat haze. That’s what Earth’s atmosphere does to starlight. By stepping into orbit, Hubble avoids that haze, capturing crisp, detailed images that revolutionized our understanding of the universe. It showed us that galaxies aren’t just static smears—they’re vibrant ecosystems of birth and death, home to swirling gas clouds, newborn stars, and violent supernovae. The iconic “Pillars of Creation”? That’s Hubble’s handiwork. It took invisible grandeur and made it visible and familiar.

This is an artist’s impression of a young star surrounded by a disk of gas and dust. An international team of astronomers has used NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope to study the disk around a young and very low-mass star known as ISO-ChaI 147. The results reveal the richest hydrocarbon chemistry seen to date in a protoplanetary disk.

But that’s just part of the story. When we look at galaxies billions of light years away, we’re actually looking back in time, because the light from those galaxies can take billions of years to travel here. Over such immense stretches, the very fabric of space expands, stretching the light into longer, redder wavelengths.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s high resolution, near-infrared look at Herbig-Haro 211 reveals exquisite detail of the outflow of a young star, an infantile analogue of our Sun. Herbig-Haro objects are formed when stellar winds or jets of gas spewing from newborn stars form shock waves colliding with nearby gas and dust at high speeds. The image showcases a series of bow shocks to the southeast (lower-left) and northwest (upper-right) as well as the narrow bipolar jet that powers them in unprecedented detail. Molecules excited by the turbulent conditions, including molecular hydrogen, carbon monoxide and silicon monoxide, emit infrared light, collected by Webb, that map out the structure of the outflows.

Early galaxies and some of the universe’s earliest stars don’t just appear faint—they’ve literally had their light shifted out of Hubble’s comfortable visible range and into the infrared. Hubble tries its best, and it does have some infrared capabilities, but it’s not optimized for this. It’s like trying to taste subtle differences between ingredients while wearing a thick blindfold over your nose. You might get hints, but you can’t fully savor the complexity.

NGC 346, shown here in this image from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam), is a dynamic star cluster that lies within a nebula 200,000 light years away. Webb reveals the presence of many more building blocks than previously expected, not only for stars, but also planets, in the form of clouds packed with dust and hydrogen. The plumes and arcs of gas in this image contains two types of hydrogen. The pink gas represents energized hydrogen, which is typically as hot as around 10,000 °C (approximately 18,000 °F) or more, while the more orange gas represents dense, molecular hydrogen, which is much colder at around -200 °C or less (approximately -300 °F), and associated dust. The colder gas provides an excellent environment for stars to form, and, as they do, they change the environment around them. The effect of this is seen in the various ridges throughout, which are created as the light of these young stars breaks down the dense clouds. The many pillars of glowing gas show the effects of this stellar erosion throughout the region. In this image blue was assigned to the wavelength of 2.0 microns (F200W), green was assigned to 2.77 microns (F277W), orange was assigned to 3.35 microns (F335M), and red was assigned to 4.44 microns (F444W).

That’s why we built the James Webb Space Telescope. Its destiny was to become an archaeologist of light, a time-traveling historian that can read the faded ink of the universe’s oldest chapters. To do that, Webb needs to be utterly, fantastically cold. Why? Because infrared is basically heat radiation. If Webb were warm, it would glow in the infrared itself, drowning out the faint signals it’s trying to detect.

(Image 1 of 2) This image from Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) shows a group of galaxies, including a large distorted ring-shaped galaxy known as the Cartwheel. The Cartwheel Galaxy, located 500 million light-years away in the Sculptor constellation, is composed of a bright inner ring and an active outer ring. While this outer ring has a lot of star formation, the dusty area in between reveals many stars and star clusters.

(Image 2 of 2) This image of the Cartwheel and its companion galaxies is a composite from Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), which reveals details that are difficult to see in the individual images alone. This galaxy formed as the result of a high-speed collision that occurred about 400 million years ago. The Cartwheel is composed of two rings, a bright inner ring and a colorful outer ring. Both rings expand outward from the center of the collision like shockwaves.

So Webb is stationed about 1.5 million kilometers away, at the Earth-Sun L2 point, a gravitational sweet spot. There, it holds a giant five-layer sunshield, a tennis-court-sized parasol that cools it down to temperatures colder than the frigid depths of Pluto’s neighborhood. By doing this, Webb can detect faint infrared signatures that are billions of years old—light emitted by stars and galaxies when the universe was a tiny fraction of its current age.

The distorted spiral galaxy at center, the Penguin, and the compact elliptical at left, the Egg, are locked in an active embrace. This near- and mid-infrared image combines data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument), and marks the telescope’s second year of science. Webb’s view shows that their interaction is marked by a glow of scattered stars represented in blue. Known jointly as Arp 142, the galaxies made their first pass by one another between 25 and 75 million years ago, causing “fireworks,” or new star formation, in the Penguin. The galaxies are approximately the same mass, which is why one hasn’t consumed the other.

Now, think about what this means. While Hubble gave us a detailed portrait of galaxies as they looked relatively “recently” (a few billion years in cosmic terms), Webb tunes into the embryonic times of the cosmos, capturing galaxies when they were infants, mere hundreds of millions of years old. This is critical because it’s like reading the introduction and earliest pages of the universe’s autobiography.

In this mosaic image stretching 340 light-years across, Webb’s Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) displays the Tarantula Nebula star-forming region in a new light, including tens of thousands of never-before-seen young stars that were previously shrouded in cosmic dust. The most active region appears to sparkle with massive young stars, appearing pale blue.

Before Webb, we could guess what the earliest galaxies looked like, but we had no direct window into that epoch. With Webb, we can study how the first galaxies formed, how they differed from today’s galaxies, and how the seeds of modern structure were sown. It’s like we knew the middle and the end of a mystery novel, but finally got to crack open the prologue.

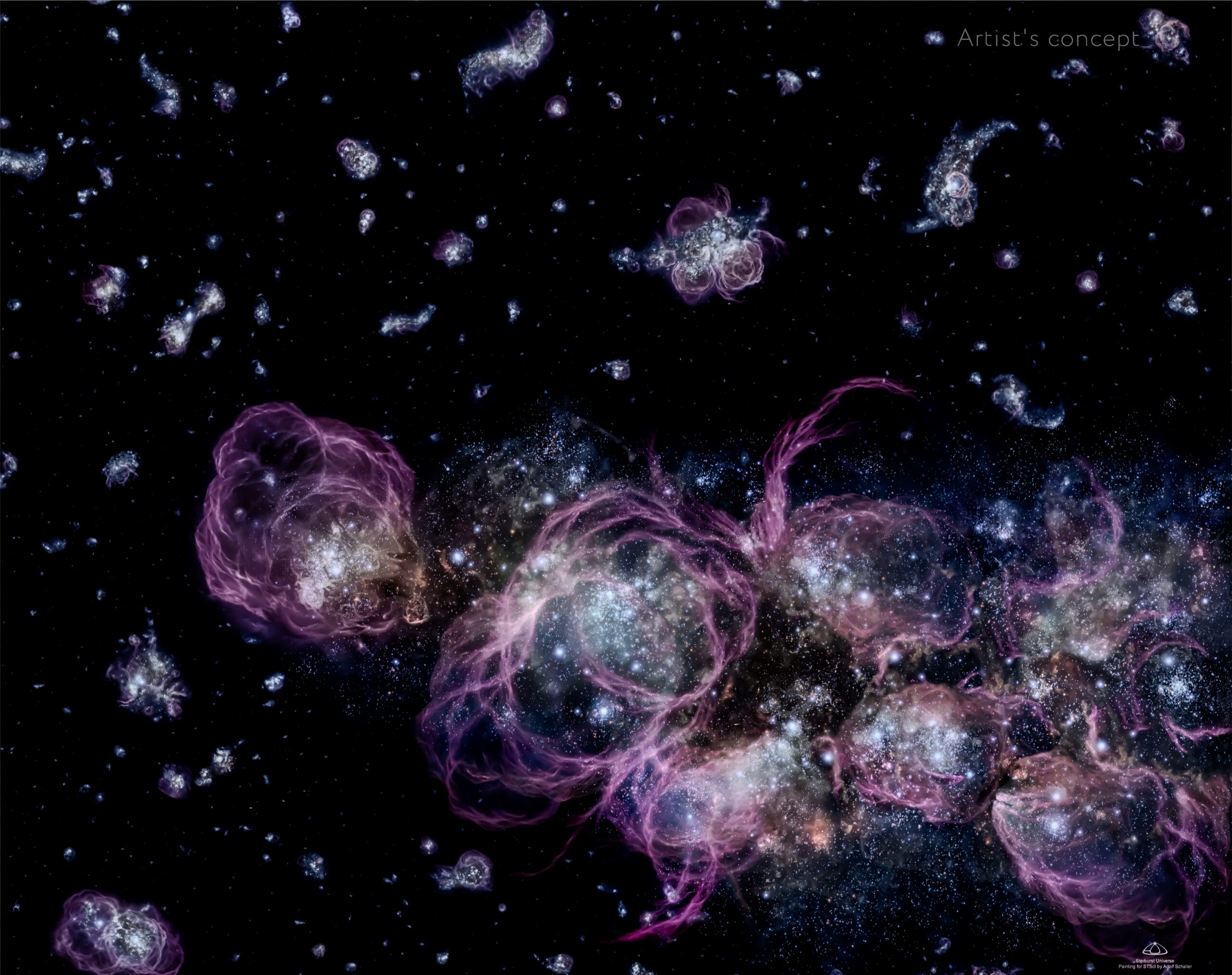

This illustration shows a galaxy forming only a few hundred million years after the big bang, when gas was a mix of transparent and opaque during the Era of Reionization. Data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope shows that cold gas is falling onto these galaxies.

But that’s not all. Webb’s infrared vision also allows it to peer through dust. Space isn’t empty—it’s full of tiny particles that block visible light. Regions where stars are born, for instance, can be shrouded by cosmic dust. Hubble can see the beautiful glow of these star-forming regions, but Webb can actually look inside the dusty cocoons, unveiling details of how stars and planetary systems are nurtured. It’s as if Hubble showed you a closed suitcase and said, “Look, it’s a suitcase!” while Webb opens it up, examines what’s inside, and notes how neatly folded the socks are.

This image of the Orion nebula, the brightest spot in the sword of the constellation Orion, shows carbon-rich molecules called polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) as wisps of red and orange. This image was captured through a team-up of the Hubble and Spitzer telescopes, two predecessors of the James Webb Space Telescope. “With Webb we’ll be able to see far more detail, including variation in the wisps of PAHs that we currently must paint with a relatively broad brush,” said Christiaan Boersma, an astronomer at Ames and joint principal investigator on a project that will use Webb to study PAHs. Boersma is an extended core team member on a Webb Early Release Science project studying this exact region in Orion.

Additionally, Webb can probe the atmospheres of exoplanets—worlds orbiting other stars. When a planet passes in front of its star, starlight filters through the planet’s atmosphere. Different molecules absorb specific infrared signatures, allowing Webb to decode a world’s chemical recipe. Before Webb, this kind of analysis was possible, but far less precise. Now, not only can we detect interesting molecules—maybe even the building blocks of life—but we can do it with unprecedented detail, in wavelengths Hubble only skimmed.

In this sense, Hubble and Webb aren’t competing—they’re partnering. They are complementary parts of a grand cosmic detective agency. Hubble gives us the crisp “here and now” vision and some glimpses into the past. Webb reads the faint, deep past, tells us the origin stories of galaxies, and deciphers molecular signatures hidden in cosmic corners. Working together, these telescopes fill in the gaps, each providing clues the other can’t. They are two instruments expanding the boundaries of what we consider knowable, unveiling layers of a universe that’s never just one thing, but many overlapping stories woven together by light and time.

Ultimately, what makes both Hubble and Webb so profoundly important is that they remind us that the universe is bigger, older, and stranger than we might have imagined. With Hubble, we learned that our cosmic home is teeming with variety and drama. With Webb, we are learning how all that began, how the very first cosmic structures took shape, and what secrets might be hidden in distant worlds. They’re showing us that seeing is not just believing—it’s learning, growing, and understanding ourselves better. Because the more we discover out there, the more we understand what it means to be here, looking up, listening to those whispers of light echoing across eons.

More from Astronomy

What’s the Human Protocol for Alien Contact? Are We Really Prepared?

What do we do if we Make Contact with Aliens If we someday pick up a signal from intelligent life beyond …

Panspermia: Did We Come From Another Planet?

Here is an interesting thought experiment: what if life didn’t start on Earth? What if we’re all... aliens? This brings us …